How to Do a Zoning Analysis, Part 2

Expertise matters.

Last week, I posted Part 1 of “How to Do a Zoning Analysis,” so if you haven’t read that one, do that first. This article picks up where the last one left off.

6. Set up an excel spreadsheet

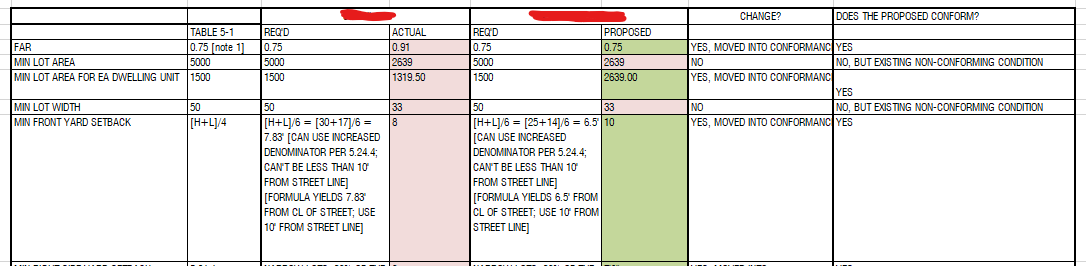

Using the dimensional requirements you looked up in #3, create a spreadsheet listing each item, creating columns for required, existing, proposed, change?, and does the proposed conform? Fill in the "required" section, as that will be straight from the ordinance. Using your survey, fill in the "existing" section, highlighting any block that doesn't conform. Remember that some zoning requirements are minimums and some are maximums, so make sure you're keeping them straight!

The "proposed" section is where you'll play with what you'd like to do in the project, and where you can keep an eye on where you might need variances. The "change?" section is where you can show the zoning official, very clearly, where you're making any changes. The goal of a zoning analysis is not just to figure out what's possible, but ultimately, to document what you did so that the zoning officer can clearly see it during their review. Confusion or lack of clarity is *not* helpful for your application!

And then finally, "does the proposed conform" should be a yes, no, or existing non-conforming. Again, the goal here is clarity - both for yourself as you analyze, and for the zoning official who will [hopefully!] be reviewing your submission should you decide to pursue the project. If you're looking at multiple parcels and running multiple scenarios, it's also very important to keep these charts clear - you don't want to mix up your projects!

7. Determine your buildable area[s]

Using your survey as an underlay, begin mapping the information you've compiled in your spreadsheet. Indicate your setbacks, required distances and separations, allowable areas for parking, etc. If it's a lot with a building on it already, indicate graphically any area that is existing non-conforming. Make sure you review all of the provisions of the dimensional requirements from Step 6, and how they interact on your lot. Take notes on anything that's confusing, or contradictory, or a unique condition.

You may need to do a section or elevation diagram as well, indicating height or area/volume information in the existing, proposed, and required conditions.

8. Begin laying out your options

Now that you know what you can and can't do, and have it mapped out on your lot, you can begin figuring out how that manifests itself in a built form. If you've got a required height setback above a certain number of stories, for example, and you combine that with required side setbacks, do you still have a usable building floorplate on those stories?

At this point, we often start with laying out egress stairs and elevators. To understand whether a site is worth a dang, we need to understand how the allowable floorplate size works with required egress rules. This is where a good architect really shines, combining code knowledge with knowledge of how to layout actual useable units - and where reliance on purely engineering solutions can leave you up the creek.

For example, there may be 100 ways to make egress “work” on a lot within the given zoning parameters, but 87 of them result in weird unit layouts, wasted space, or other code issues [dead end corridors, not enough room for an elevator lobby, weird first floor layout, issues with parking relationship to egress, not enough room for required support spaces like loading docks, trash room, electrical vaults, etc]

We also want to keep the building's "net to gross" ratio as high as possible. This ratio compares non-rentable/salable spaces like hallways, amenity spaces, support spaces, stairs, etc with spaces that are rentable/salable like units, commercial tenant spaces, etc. The goal is to get as many square feet as possible into the rentable/salable category as we can - basically, to have an efficient building without a bunch of long hallways. This takes a lot of design and code know-how that architects - not civil engineers or zoning attorneys or contractors - are best at.

9. Track your options in a spreadsheet

Pretty soon, you'll start to have several different options going - keep track of them, as separate drawings/diagrams, and as separate lines in your spreadsheet. What does it look like to do a project with no parking? How about with all small units? What about all larger/family sized units? This is where the design/zoning analysis stuff overlaps with market forces and the developer's proforma - and where the architect-developer relationship really shines.

The back and forth between those architects who really know how to layout a building at this stage [and who are aware of and sensitive to the needs of the developer] and those developers who really know their markets and understand what they need to make a building perform [and who are aware of and sensitive to the realities of zoning, code, and the realities of construction] is fun, fruitful, and exciting.

10. Determine which option to move forward with

Yes, you eventually have to make a decision! And this is squarely on the developer's [or homeowner’s] shoulders. No one else can decide for the owner which option to pursue - because ultimately, it's the owner's project. No single option will be cut and dry - one might be really great for the proforma but requires some tricky zoning variances, while one might perform less well financially but is by-right and will be easier to permit. These are the tough decisions that owners have to make, and live with - but they're a helluva lot easier to make and to live with when there's good analysis at hand.

PS - Don’t forget other processes

We’ve focused mostly on zoning analysis here, but there are also other pre-permitting processes you might have to go through, as well - historic commissions, development review boards, site plan reviews, etc - that may be part of your jurisdiction’s zoning process, or might be entirely separate. So…make sure you’re accounting for those processes, too!

Conclusion

I've come across plenty of developers who skimp on this process. In a hot market, maybe that's possible - it's easier to cover up mistakes and slop when everything is moving well in the market. But when times get tougher, analysis needs to get tighter. And even in a hot market, no one wants to lose money on a foolish project.

Think about how much a project will cost, and what the financial implications are - and how much you'd spend to know that the project was a good one, that there'd be no surprise zoning provisions lurking just around the corner, ready to cause big delays and big cost overruns. It's small money...even in pre-development stages when money is tighter.

And, I’ve come across developers who have an encyclopedic knowledge of zoning, coming from years of working in the same jurisdiction, knowing the zoning officers by name, and being good to work with in the building community. Those folks are a joy to work with, because they focus on the long game. They inspire - and expect - their consultants to bring their A-game to every zoning study.

So if you're a developer, find a good architect who can do this kind of work, preferably someone local to the jurisdiction you're working in. Not all of them can do this kind of work. And, pay them. Don't say "if this project goes forward, you'll get a chance to be the architect." If you want them to accept financial risk, then you need to change your compensation model to account for that. Just pay them for their services. Don't rely on a civil engineer, especially on tight urban sites.

If you're an architect, hone your skills to deliver the right amount of information. Don't give 1000 options, don't spin your wheels and burn fee iterating unnecessarily or getting too far into design too early. Find out what is important to the developer, and get them a viable project first. And, be the voice for others who aren't at the table.

As always, thank you so much for reading, and supporting this work! It takes real time to put this together, and my goal is to bring you real value! If you feel so inclined, consider sharing a subscription or referring someone you think might enjoy this content.

And if you’re interested in working together, drop me a line by replying to this email! We do consulting work for owners and developers all the time.

And last but not least, this is not legal advice. None of my posts are. Make sure you’re working with professionals who know the laws and ordinances in your jurisdiction.