Comparing Construction Estimates: 9 Things

The mantra: Apples to Apples!!

When you’re comparing construction estimates - for projects of any size - there are many things to consider. The single most important thing is to get to an “apples to apples” comparison of bids, so that what you’re comparing is…well…comparable!

As soon as everyone gets an estimate of any kind, they scroll to the bottom, straight for that number, skipping all the explanation, exceptions, etc, and they have a reaction to that number. “WHOA that’s too much money compared to the other guys!!” they might think, while totally missing that the other guys ignored or misunderstood the drawings and missed some very important costs.

So, how do you compare bids?

As I’m always saying, estimating is just as much art as science…and it takes a long time to develop intuition around when something is a fair/accurate price. That said, here are a few things I’ve learned over the years [starting in my years as an estimator/project manager at a GC] and reading 1000s of bids over the last 20 years.

Create a “normalization spreadsheet”

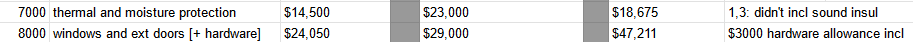

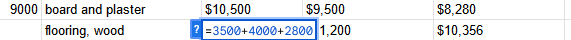

Take all the estimates, and compare them line item by line item, in a spreadsheet. You may be thinking “duh!” but this single task can take quite a while when you dig in - you’ll generate a ton of questions, you’ll find stuff that one person missed and another one caught, etc. Make sure to take notes on each category, so you remember who included what, or you remind yourself to ask the GC for clarification.

In the example below, the middle GC included sound insulation but the first and third didn’t, which helps explain the discrepancy. I also noted that all three *did* include a $3000 hardware allowance in the windows/doors line item.

Take notes on each line item, and if you group more than one cost category into a cell, make a formula with each item included individually, so you remember later what you grouped into that category. In the example below, the three numbers in that formula include the flooring material, labor, and finishing as three numbers that add to a total cost for the wood flooring.

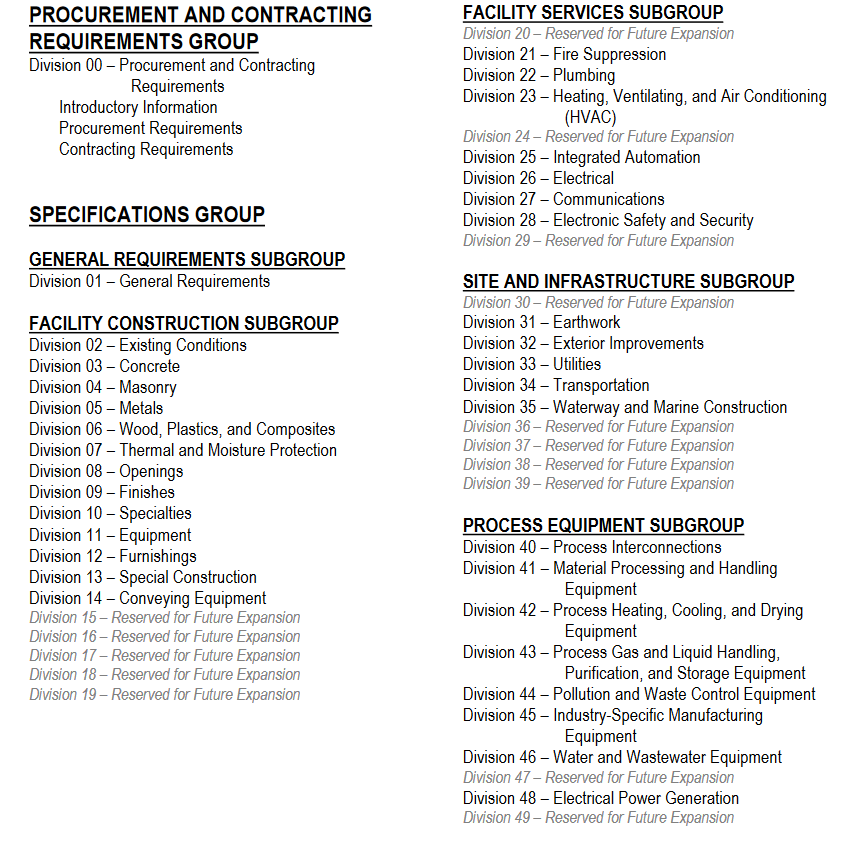

Use MasterSpec numbers to organize your spreadsheets

MasterSpec is a numbering system that assigns industry-wide numbers to every aspect of a construction project. Often colloquially known as the “16 divisions,” after the [now outdated] list of 16 categories of construction, it’s a way to group and organize construction projects, schedules, and estimates. These days, there are a lot more than 16 divisions, but the concept still holds: the first digit of the 4-digit MasterSpec number indicates the division/broad category, and each number after that narrows the category further.

Specification organization and MasterSpec is a whole ‘nother post, so we’ll dive further into it in a future post!

In the examples above, you can see that I used the broad category numbers [7000 for Thermal and Moisture Protection, 8000 for Windows/Doors, and 9000 for Finishes] to group items in my spreadsheet. Ideally, the contractors will give you estimates with everything already categorized like this, so you can easily compare…but they usually don’t, or there are nuances to how they group things, or they make up their own method…so that’s why we need to make this spreadsheet!

How is the markup distributed?

In a cost-plus or time and materials estimate, the GC charges a straight markup on the subs and materials, and an hourly rate for their crews and staff. This is a common approach for renovation projects where it’s impossible to know all of the potential issues lurking behind walls ahead of time [and therefore it's impossible to fix a fair price], or on projects where there are a lot of unknowns in the design. [Contract structure - cost plus vs fixed price vs GMP, etc - is another whole 'nother post!]

I like to see OH/P [overhead and profit] as a separate line item at the bottom of the estimate, but many GCs like to distribute it throughout the estimate on each line item. GCs like it because there's often a strong psychological reaction from potential clients to seeing a big fat number at the end of the estimate labeled "profit." The sneaky ones like it because they can fudge numbers more easily.

I prefer to see it as a separate line item so we can more clearly understand the actual costs of the subs and materials. The discussion of what percentage the GC will get for OH/P is a separate conversation/negotiation, which is much harder to have when it's all squished together and hidden throughout the estimate.

Where is labor for each item?

Everything on a construction project has both labor and material costs associated with it, but because of how subcontractors work, there might be some confusing crossover. For example, framers usually set the windows, so that labor number is captured and rolled up into the framing labor number, but the cost of the windows themselves is under the "windows and doors" category.

Similarly rough framers might install the stair stringers, but the finish carpenters might trim out the stair and install risers/treads, and a stair specialist might be brought in to install specialty railings. All of those things might be considered "stairs" but their labor is captured by several different subs, who are also doing other things.

This is why construction cost estimating is complicated - when you ask to add or subtract a scope of work, it may touch several subs in several line items, impacting timing, management, and work flow.

As you're comparing numbers, make sure you know where labor for every item is included!

Level of detail of the estimate

Are you looking at a ballpark estimate, or a hard bid? When you're first talking with GCs about estimating the job, be clear what level of detail you're looking for. And - this is really important - provide them with the appropriate amount of information to facilitate that level of detail! If you're asking for a hard bid but gave them preliminary sketches, you aren't getting a hard bid - it's just not possible.

The GC can only give you as good/detailed of an estimate as the level of detail you provide them at the outset - which is why good drawings, clear selections, and a written scope is super important. If you're doing walkthroughs and just discussing verbally what you want to do, expect that the estimates will vary widely, based on each GC's interpretation of what you said.

When you're comparing the bids, keep this level of detail in mind, and don't expect to have conversations about how many boxes of screws they've included in the estimate when you just provided them with outline plans.

I've seen projects fall apart when owners lose sight of this - on a $1.5m project, a client getting worked up about a $1k line item, not giving the GC the job, going with the cheaper/less experienced guy, then spending many times than that because of mistakes and delays by that guy....don't make that mistake. Calibrate your expectations, and provide good information, and don’t get lost in the wrong scale of detail at the wrong time.

Don't forget about duration

Just as important as the bottom line number is the amount of time the project will take. Time is money...and if you're seduced by the cheaper guy without realizing he's going to take an extra 6 months, you're further in the hole than if you went with the guy who had his act together.

Compare how each GC answers the duration question - that's also just as important as the number they say. "Well, it should take anywhere from 6 to 8 to 14 months" is not a good answer. Ask what the largest contributors in the project are to the duration - what design decisions are adding the most time? If you keep getting the same answer, and you're needing to cut some time from the project, you may need to take a closer look at whether that cool design element is worth the time.

That said, sometimes GCs will push back against design elements that they're not used to or don't want to do, and will tell you it takes a really long time or is really expensive just so you'll cut it from the project and make their job easier. A good architect who understands construction is key here - they can push back appropriately here, and help the GC understand the vision and how it can be done.

Lurking fees

Make sure you understand what fees might apply to your project - every jurisdiction assesses permit fees differently, for example, and if you are adding/modifying utilities, there will be fees associated with those as well. Some jurisdictions assess building permit fees on a percentage of project cost, which you estimate at the beginning of the project. Usually, you also have to submit a "cost affidavit" at the end with the final costs, so the city can get their cut on the full cost of the project, not just your estimate.

Utility hookup fees can be very expensive, along with required local/state inspections for elevators, pressure vessels, sprinkler systems, flow tests, etc - all of these things add time and cost to a project, and will apply differently depending on size or type of project.

Parking fees is another sneaky one - in big cities or tight sites, you will likely have to pay for a lot of parking tickets, special parking permits, police details for when large deliveries come in, street/sidewalk closures, etc. Make sure stuff like this is included, because it’s real.

A good GC should include the fees they expect to see on a project like yours, and should indicate those clearly in their estimate.

Contingency

For custom residential renovations, I advise clients to hold a 25-30% contingency off to the side to handle unforeseen issues and surprises. At no time should the GC's number be an owner's max project budget - there are many costs above and beyond that need to be factored in.

Some GCs include a contingency in their estimates, or require an owner to provide proof of funds of a contingency of a certain size, so they have assurance that the owner can handle bumps in the road during construction. All of this is negotiable, and the bigger the project, the more formalized that will get.

When you're comparing bids, you just want to make sure you're comparing things fairly. If one GC included a contingency, but the other two didn't, it's going to make that first one look very skewed. Use your normalization spreadsheet to balance things like this out.

Allowances

"Allowances" are placeholder dollar amounts for line items that haven't been selected yet, but that must be included. Many finishes and fixtures are handled this way - when you're getting preliminary bids, you likely don't have all the plumbing fixtures or tile picked out, but you still want to account for them in the budget. So, you assign a placeholder to that line item.

Allowances function as "mini cost-plus" parts of the contract, meaning if there's a $5k allowance for interior door hardware, but the owner spends $7k, the owner is on the hook for the extra $2k. Conversely, if they only spend $4k, they don't have to pay $5k. It's a floating placeholder.

I prefer to give the GCs actual allowance numbers for as many line items as I can, because 1. it levels the playing field, 2. I have a good sense for what the client is going to select in terms of price point, and 3. I have a solid sense of what most finishes cost for the clients and projects I typically work on. GCs are generally relieved that I provide these, as it takes the pressure off them, and they know the other GCs will be using the same numbers for all these line items.

Even when you give them the info, though, you need to check a few things. First, did they include their markup on top of the allowance, or inside the allowance? This can have major implications. For example, if I indicated they should use $40k for plumbing fixtures, and GC #1 includes their 20% markup in that number, that means I only have about $33,500 to buy the fixtures with, but the bottom line looks better. If GC #2 puts markup on top of the $40k, the bottom line is $8k higher, but I have the full $40k that I asked for to shop for plumbing fixtures.

Spread across many different fixtures and finishes, you can see how quickly that differential would add up!

And also, it's easy to see that the fewer allowances there are - meaning, more stuff is selected and picked out and not left til later to figure out - the more accurate and detailed the price can be.

Conclusion

The more you understand how construction works, and the better information you give GCs, and the better the team around you, the better you’ll be able to assess and compare bids and estimates.

As usual, this post just scratches the surface - there are many more strategies, and I probably could [should?!] do 5 more posts on this topic alone! What are some of your favorite techniques for comparing estimates?

As always, thank you for reading, and for your support! If you know someone who’d be interested, let them know!

This is great! Agree on allowances. I love inputting this on my CM jobs... often I may begin with a big bundled number and in the second round I'll give myself specific allowances per item/fixture... then eventually we pick em.