8 Things to Include in a Bid Set, 5 Things That Don't Matter

Get better bids by giving better info to the contractors

The best way to get the most accurate numbers from a contractor during the bid phase is to include as much *relevant* information as you can. You don’t want to overwhelm them with drawings and pages and pages of narrative. Every drawing, every sentence, should be relevant, clear, succint.

[Note: This post is focused on projects that are getting early bids - so, not full, hard bids of the completed construction documents, or projects that go through a formal or public bid process. That’s a whole ‘nother process, and not what I’m talking about here.]

The goal is to say as much as possible with as few materials as possible. It’s respectful of the contractor’s time, and it’s less costly in terms of design fees. We’re aiming for “better than a ballpark” estimate, but not the “this is your exact assigned seat in the ballpark” estimate.

To that end, we bid projects early - whether they’re a custom home or a multifamily project. Armed with that, we have a sense of costs as we’re designing, but we want to make sure we’re not going too far down the line into the design phase without getting real gut-checks from contractors.

On our residential projects, that usually means getting bids from three different contractors. That allows us to get an early look at the contenders, and get one onboard early enough to actually help and collaborate with us on the design.

[To learn more about our residential deisgn process, which is a bit different than the “industry normal” way of doing things, click here.]

On our multifamily, commercial, or industrial projects, when and how we get initial bids really depends on the project itself. But no matter what, we always try to get something as early as possible!

One thing I learned while working as a construction estimator is that a lot of the early bidding phase is, for lack of better terminology, about the vibes. Is the vibe of the project scrappy or full paperwork? Is it relaxed or under the gun? Does the team feel decisive or wishy-washy? Is the tile from Home Depot or Ann Sacks [or custom from a certain quarry in Italy]? Are the appliances Sub Zero/Wolf or GE/Bosch or scratch and dent? Are the plumbing fixtures Delta or Waterworks?

You get what I’m saying. With a few questions like that, a GC or estimator can get the feel of the team, the project, and the price point pretty dang fast, and can extrapolate from there. What you as owner/design team want to do is make sure you’re providing those outline parameters so the GC knows where on the spectrum to price the overall project.

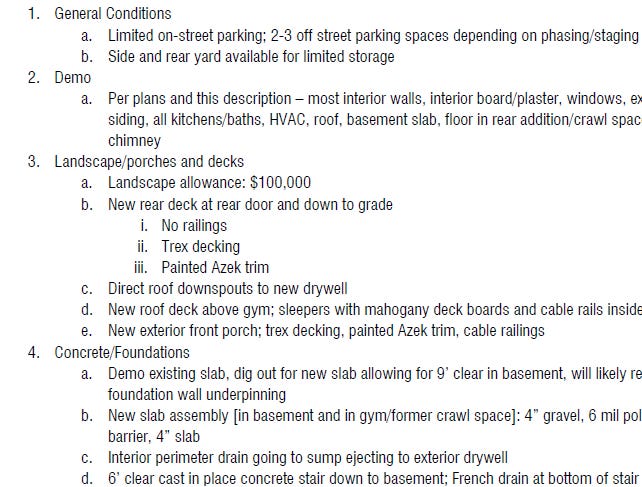

In bid sets we provide to contractors, we usually have just a few drawings, and the star of the show is a written outline specification, including many of the items listed below [note that this list isn’t exhaustive, and may differ for your project!]:

Parking/site access: One of the biggest cost drivers of a project is how easy or how difficult it is to access, store materials, pull in a dumpster, have all the subs park onsite, and the like. It’s why projects on tight urban sites cost so much - everything takes longer and takes that much more coordination. That’s why you need to make sure that folks bidding the job understand these parameters clearly. They should be able to see stuff like turning radii and parking capacity on a site visit, but in your narrative, include information about allowed working hours, neighborhood restrictions, client requirements [“don’t drive under the oak tree” or “don’t park on the hardscape”], elevator access/loading, etc.

Client expectations: Make sure to include information about special requirements the client has - working hours, dust/noise control, working with certain subs [and/or not working with certain others], deadlines - a lot of this will depend on the type of project. A residential remodel with a client who’s living there will have quite a few requirements, and the GC needs to know what those are. The client also needs to understand that the more requirements they have, the more the GC will charge! Other considerations might be around deadlines [a rental building finishing in time to hit the leasing cycle at a favorable time], social media [the client may want to film or document the project for marketing purposes, for instance], and the like.

MEP narrative: For a small project, the client/architect can write this themselves, including information about which systems will be replaced vs repaired, and the extents of the work. For larger projects, it’s best to make sure the MEP engineers are engaged early enough - and have their heads in the actual project deeply enough - that they can provide a few paragraphs of information for the GC. Things like power sources [gas vs electricity], types of systems, performance expectations, location of utilities and internal support spaces like electrical rooms or sprinkler rooms, and some basics on a sprinkler system/fire alarm system are all important, and get the GC pointed in the right direction.

Finish allowances: This should be a list included in the bid narrative, and based on the design team’s historic data. I know what my cabinet guy charges, because we’ve worked together on the past ten projects, for example, so I can provide that number to the contractor. Same goes for tile, bathroom vanities, plumbing fixtures, and the like. We know the “vibe” [there’s that word again] of the project, and can provide these parameters to the contractor. They then pick up on that vibe, and use it to extrapolate further.

Demo plans and narrative: A demo plan is a powerful, quick graphic to explain the extents of the work. Demo isn’t usually a large line item in the budget, but it is the best inidcator of how much work will follow. Include any information in the narrative about substances that will require remediation [lead, asbestos, etc] - there is no use hiding this or pretending, and you want to know early what the impact will be. Discuss with the contractor whether the project will be able to use dumpsters, or will have to live load, and what special equipment, protection for neighboring buildings, and/or permissions might be needed. You as owner or architect don’t have to know this information, but you should be asking the questions to prompt the GC’s thoughts!

Exterior elevations: These can be very simple - just outline drawings that allow the GC to get takeoffs of all areas, to account for materials. You can include the list of materials in the narrative - no need to draw out bricks or siding or whatnot in the drawings. You can even skip these altogether if you give the GC a sense of how much of each material you’ll be using on the facade [“cladding will be a mix of 50% Hardi siding, 40% face brick, and 10% split face CMU”]. They’re looking for an understanding of what trades they’ll need, how much of each area they need to do, where it’s located [is it high work, will it be done on pump jacks or full scaffolding over a sidewalk, etc], and what the trim strategy is. With some basic information, the GC can give a good ballpark here - but don’t forget to include special considerations like your fancy entry canopy, roof decks, built in planters by the front entrance, etc. Remember, vibes.

Special contract provisions: This one is about the management and administration of the project - you want the GC to know early if you have to use a certain contract they may not be familiar with [happens a lot in residential, where we like them to use the AIA contracts, and they’d prefer to use their internal/homegrown contracts], or if you’ll be requiring certain provisions around billing, architect involvement, procurement, engaging subs, etc. As owners do more projects, they learn more about what stuff matters to them in a contract, and what doesn’t - and that varies from owner to owner and job to job. If you’re working on developing a relationship with a GC, and you have non-starters in this department, you need to bring them up early - but also in a way that doesn’t make you appear inflexible or fussy. Tread carefully here, but don’t compromise if you don’t want to. And consult your lawyer!!

Landscape allowance: On residential projects, we often just provide an allowance number for the GC to include in their bid. It’s often so early in the project that we don’t even have a landscape architect yet, and/or the owners might be doing landscape themselves or well after the construction is complete. For commercial/multifamily projects, we include a narrative description, and ask the GC to include an allowance in their bid.

Bonus: A note about allowances. As you’ve seen, sometimes we give the allowance number to the contractor, and sometimes we ask them to provide it. If we have confidence in our ability to predict a reasonable allowance, we just provide it to the contractor, which is usually quite appreciated. On scopes of work where we’re not as confident - because we don’t have a lot of experience with that line item, or not enough historic internal data to go on - we ask the contractor to provide it instead.

Now, time for the things that don’t matter. Let’s be clear, here - some of these may matter a quite a bit for your project, so make sure you’re thinking about your particular project and its needs. I’m generalizing of course, and you need to work with your team to ensure you’re providing the right information and not getting yourself into trouble.

Cabinetry layout. If you’ve given an allowance above, there’s no need to show which walls get full height cabinets vs uppers/lowers, or where there are drawers vs doors. All this stuff affects pricing, but if you’re experienced and relatively confident in your allowance numbers, save time here by not bothering with a layout.

Lighting layout. Don’t bother giving a full layout of every fixture. Instead, indicate which areas get new ceiling [and what type], and which areas must keep an existing ceiling. Keeping the existing ceiling usually means greatly increased costs for the electrician, as it just takes longer to do their work. Then, give fixture types and counts - as in, “20 LED recessed puck lights in kitchen.” Include an outline spec of fixture types [“contractor grade LED puck lights” for example], and indicate which types the owner will supply themselves [“dining room chandelier supplied by Owner].

Interior elevations. It’s too early for these. For finishes that might need to be included in a per square foot takeoff, like tile on walls, indicate that in the narrative - “tile wainscot on fixture wall in bathroom, 42” high.” No need to make a drawing to convey what can be said with a few words.

And most basically…anything where words will suffice and no drawing is needed. We’ll get into drawings later, when we’re creating the actual construction documents. But for now…surprisingly few drawings are needed.

Your prima donna tendencies: Leave these out! Remember that in initial stages, especially a contractor you haven’t worked with before is pricing *you.* If you as owner or architect seem like a pain to work with, then the bid you get will be priced accordingly.

So there you have it - some things we always include in our bid sets, and things we don’t bother with. Depending on the project [and the client and the contractor], these lists might change, but the general idea is to get the contractor pointed in the right direction.

And as always, please consult professionals who are familiar with the project’s jurisdiction, including your attorney!

Thank you, as always, for your support! These posts come from 20 years of experience in the industry, and I’m delighted to share that hard-won knowledge with you. Please consider sharing this with others who might find it useful!